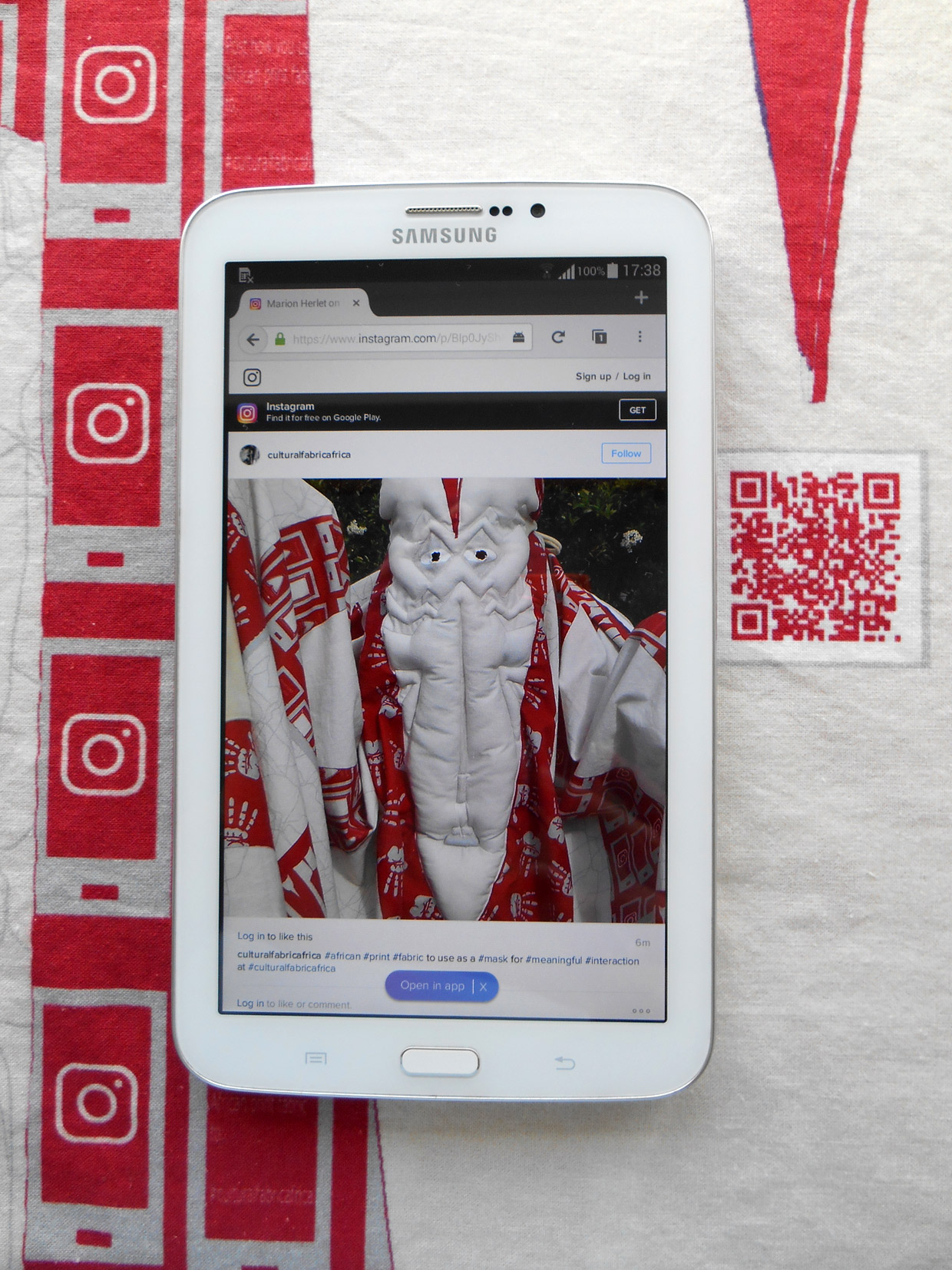

This prototype print pattern provides a key to a social media campaign. Users are invited to post images of how they use the cloth under a common Instagram hash-tag, contributing to the curation of an online platform that may open up discussion and conversation about different applications for African print fabric. The design also contains a link to the media platform which can be accessed through a QR code scanner on a mobile device.

‘Cultural Fabric Africa’ is about the potential of African print fabric to support cultural sustainability through design in the context of changing patterns of consumption.

Through informal interviews and conversations with women from the rural village in southern Mozambique in which I undertook field research in early 2016, I discovered that for special events it is custom for several women to wear the same print fabric which they also present as a gift to the person that is being celebrated. Sometimes there are two different cloth designs involved for the duration of a single event: one is worn by the women during cooking and food preparation, the other is worn for presenting the gift of cloth. Both designs are gifted in this case (Field research data: I-AJ-25.1.16). With the increasing popularity of tailoring cloth this tradition now also extends to men wearing shirts tailored from the same cloth design or simply including a small strip of that design sewn into a part of their attire. This custom is referred to as farda (Portuguese for uniform).

Observing an evident enthusiasm for social media networks like Facebook and Whatsapp amongst the younger people in the village I began to investigate how these platforms were being used. I soon came to realize that Mozambican print fabrics were heavily featured in people’s posts, mainly by making up part of their dress or attire but also emphasized as an expression of social identity and gatherings. Public Facebook groups such as ‘Capulana’ or ‘Ideas para fazer uso da Capulana’ contained numerous posts of the traditional ‘farda’ events. Was social media becoming a new form of social fabric?

After my return from Mozambique I pursued this investigation through the creation of a public Facebook group – Capulana Karingana – that explored various methods engaging people in conversations around cloth and its social functions. As an administrator of the group I would post a different print design each week over a ten week period in order to encourage people to engage with the design through stories or images. The later posts included new design ideas rather than featuring existing print patterns. In the earlier posts I solicited some of the participants who were known to me personally to post responses and by the fifth week I began to get spontaneous contributions from some of the anonymous members. The idea was to explore social media as an extension of social fabric – creating a new form of community that would connect through the digital sharing of designs.

Capulana Karingana Facebook profile – click image to visit group

Capulana Karingana Facebook profile – click image to visit group

Because Facebook did not allow me to evaluate this experiment in sufficient depth, targeted feedback questionnaires were sent to five participants of the group, all of them based in the local community where the field research had been situated. All participants expressed that they liked the group and thought it a positive initiative to learn and to promote cultural values about Capulana cloth in Mozambique (Field research data FB-CK-1/2/3/4/5). Interestingly four out of five (FB-CK-2/3/4/5) found the chequered Xadrez design – which is often considered the most traditional pattern of southern Mozambique – the least interesting design featured because it was no longer ‘fashionable’. However, two participants (FB-CK-2/3) mentioned this design as the one representing most closely local culture and traditions. One of the participants (FB-CK-1) thought this design the most interesting because of that reason whereas all the others (FB-CK-2/3/4/5) preferred representational designs of traditional objects or – in one case – a woman performing a traditional activity. It is interesting to note that all participants enjoyed those motifs that they perceived as traditional or that referred to practices of their grandparents and the elders of the community. Most participants confirmed that the designs on the cloth are important to them and that they are something that they talk about amongst each other.

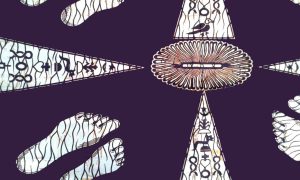

Post, Capulana Karingana, Week 3, April 2016

Post, Capulana Karingana, Week 3, April 2016

Response from group member, Capulana Karingana

Response from group member, Capulana Karingana

This experiment showed that the use of social media to share knowledge and perceptions on cultural values of print fabrics could be a potential tool to preserve and re-create such values, provided it was more easily accessible. The tendency to highlight information that linked to knowledge of the elders of a community indicated that, although they were not part of the online discussion, their oral transmissions could potentially be shared within a new community of practice. ‘It is through the communicative and connecting nature of social technology that ‘new realms of belonging’…can be established, maintained and transformed in our fragmented and diasporic world.’ (Giaccardi, 2012:26).

In an extension to these trials I investigated Instagram as an alternative platform to share meaningful stories of personal cloth patterns under a common hash-tag called #textilewithatale. Although this collaboration with a Tallinn-based textile designer did not focus specifically on African print fabrics but on textiles in general, it served to test the use of Instagram as a possible tool that could focus more on visual imagery and allow for curating a visual online platform as a way of archiving and sharing cultural heritage.

To what extent does the design invite communication and/or meaningful interaction?

This prototype is designed to create discussion and conversation through an online social media platform. It would provide an opportunity of interaction by demonstrating individual uses of cloth into a collective portal. A considerable difference of this prototype is that communication would not take place within a localized community but within a virtual community of practice.

To what extent is the design open to multiple levels of interpretation?

Because the design actually challenges the user to demonstrate and share their individual interpretation of the cloth it would facilitate multiple levels of interpretation.

How accessible is it and to whom?

Such design would only be accessible to someone who would have access to the social media platform through internet and a mobile device.

How could it be realised?

Such a design could be facilitated by designers of print fabrics but may imply an additional role of the designer as a creator and facilitator of an online space. However, the use of hashtags would make the online space accessible through a one off code rather than an individual account which would have to be maintained.

What are its limitations?

Limitations of such a design would be an unequal distribution and high levels of exclusion to access. It would also be limited to virtual communities that are removed from context of place which makes it questionable in its capacity to facilitate ‘meaningful’ human interactions.

Where to start!

Marion I really enjoyed the site – which is surprising because usually sites have poor navigation and their messages can appear dogmatic or preachy. No here though. I like the graphics, use of windows, clear heading/subheadings a great deal. The photography is professional too. I like that you ask the viewer to consider all aspects, what I usually term ‘unsociable media’ is productive and insightful. This is a ‘a virtual community of practice’ platform and is user friendly (particularly the plain English used).

! aspect that you might want to consider more though is the pale grey text, all right for me but it could prove difficult for those with perception or eyesite issues (e.g dyslexia or partial sited), this aside great stuff. Good luck!