This prototype print pattern consists of symbols that can be (re)moved through an added Velcro base on a panel of loop nylon. The symbols represent objects that are considered traditional by women of the N’komati River community in Southern Mozambique. In encouraging the user to interact with the textile, the design directs awareness to its content and introduces an element of choice that aims to generate meaningful discussion and conversation.

‘Cultural Fabric Africa’ is about the potential of African print fabric to support cultural sustainability through design in the context of changing patterns of consumption.

During field research undertaken in southern Mozambique in early 2016, one of the central discoveries has been the way representational motifs on cloth almost always lead to conversations and the recounting of stories about the featured objects. When various samples of print fabric – ranging from abstract patterns to a specific design featuring a traditional ceramic water pot – were shown to women of the village in separate interviews, the majority of them began to point out the pot and shared stories and memories about using such a vessel to preserve drinking water in the past (Field research, 2016: I-AJ-25.1.16/II-O-23.1.16/I-JM-13.1.16/I-LM-21.1.16/I-MD-22.1.16/I-RS-16.1.16/I-SC-9.1.16). Today these pots have been replaced by plastic containers to carry and contain water but the stories revealed that the pots had real advantages such as keeping the water cool and fresh for a longer time.

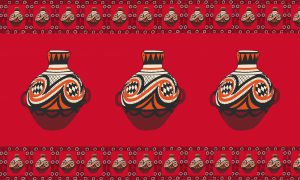

Print fabric featuring a traditional ceramic pot

Print fabric featuring a traditional ceramic pot

Realising the potential of such imagery to engage people in sharing historical narrative, lead me to coordinate a workshop in which quick prototypes of textile patterns showing various objects were displayed on a screen. Twenty participants – both men and women of different ages – were invited to comment on these images. The purpose of the exercise was to observe resulting dialogue and conversation in response to the designs. The objects featured were both objects that were considered traditional and those which – based on my assumptions – could be seen as modern replacements (see image below). The designs were first shown randomly but at the end they were directly juxtaposed.

Print fabric design with a plastic container replacing the ceramic pot

Print fabric design with a plastic container replacing the ceramic pot

I observed that most people contributed to the discussions and that the contributions were almost always based on some form of experiential memory or individual encounter with the featured object. Gender specific responses seemed to be prevalent when the object was mainly used by either women or men: women seemed to be more outspoken about those objects that could be seen as their responsibility, for example cooking utensils. There was also a noticeable difference in the opinion of the older generation when it came to objects to which only they were able to contribute experiential knowledge. These objects consequently generated conversations between the older and younger participants, with the latter asking questions and learning about objects that were no longer in use.

It also seemed that traditional objects represented on cloth satisfied various tastes: the older generation appreciated designs featuring motifs of their era, the younger generation preferred representational or ornamental designs in general (this has been also confirmed in Field research, 2016: FB-CK-1/2/3/4/5). In addition it was interesting to note that the images in which objects were juxtaposed were less effective and if anything seemed to add constrains by imposing a connection. Objects featured in isolation on the other hand solicited active responses and lead to conversations amongst the participants. (Field research, 2016: WS-5.2.16/WS-Audio/WS-Film4-6)

Limitations of this investigation included the use of a computer screen to display the designs which was challenging both in terms of the image size as well as working with a format that was new to most participants. The fleetingness of the image encounter affected levels of memory retention when trying to connect different images that were shown in sequence. Another difficulty was to decide on the kind of objects that should be displayed. Even though the choice was based on previous research in the context of the community, there was still an imposition of content defined by the featured objects in the designs.

However, when the participants were asked to suggest their own ideas for print designs the outcome was surprisingly different from the direction of previous discussions. What suddenly seemed more important were objects that were visually pleasing and highly recognized as part of peoples daily lives. This ambivalence was further confirmed by an ecological sorting exercise of a colleague who was undertaking a research study in ecology and landscape monitoring coinciding with my field trip. The same people who had participated in my workshop were invited to sort plant samples and watercolour renderings of different species of plants, birds and insects based on their uses and applications (Field research, 2016: WS-Film1/2). When asked to select the symbols they would enjoy seeing as a printed cloth design, the result did not seem to coalesce with any of their previous prioritisations. It seemed aesthetics were the main reason for their choices along with having seen similar symbols on print fabrics previously (Field research, 2016: WS-Film3). Could this lack of innovation be a result of the fact that the production of print fabrics generally does not include user participation? How then could such participation be introduced whilst still satisfying the need for aesthetics and accepted content?

Ecological sorting exercise, Marta Castiglioni, 2016

Ecological sorting exercise, Marta Castiglioni, 2016

The resulting textile prototype introduces an element of design participation by allowing the user to adjust the pattern manually through (re-)moving the featured motifs whilst still insuring that they are visually pleasing and part of a larger design composition. By inviting the user to interact with the design it seeks to create awareness of the design content and inspires content related discussion and conversation.

To what extent does the design invite communication and/or meaningful interaction?

Building on the information gathered during field research as described above, this prototype is based on evidence that representational symbols and moreover symbols that allow for user interaction could successfully invite constructive dialogue and conversation. This evidence has been further investigated through targeted feedback on representational designs featuring traditional objects in the context of rural Mozambique (FB-3PT). All four participants that were asked to submit their feedback thought that such designs would trigger conversation.

To what extent is the design open to multiple levels of interpretation?

Because the symbols are interchangeable the cloth would be able to adapt to different local contexts and interpretations. Although suggesting a certain content through the chosen motifs, the fact that they can be removed introduces an element of flexibility.

How accessible is it and to whom?

Such design could be used in the context of any community familiar with African print fabrics and would be accessible to all. It would not require the use of any additional tools or skills.

How could it be realised?

The use of loop nylon and Velcro would require an additional step during the cloth production stage which would therefore be a design proposition that would have to be taken on by a cloth producer. However, there may be other solutions such as textile designs that might suggest similar interaction with the material through patchwork for example, allowing parts of the print pattern to be cut out and sewn onto the cloth elsewhere.

What are its limitations?

An important aspect to consider would be the extent to which such a design could still satisfy the users sense of aesthetic and sophistication. It would also be questionable whether materials such as loop nylon and Velcro would allow the cloth to be used as attire or for other desirable applications.

It is beautiful idea and well executed. I’d be curious to see the follow up touching another culture with different symbols. Whether the interaction would remain the same or appear to be different.