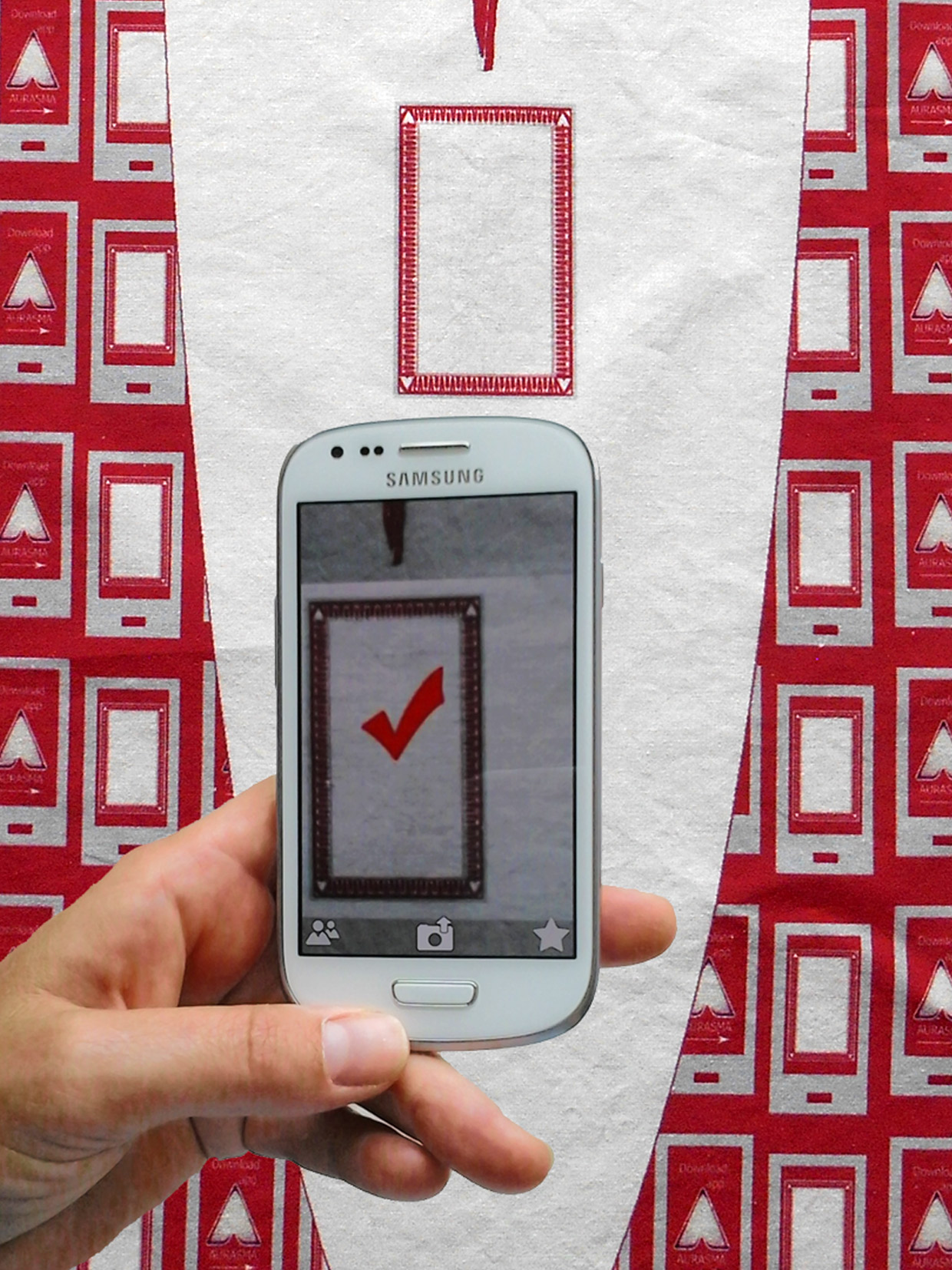

This prototype print pattern shows a frame that contains a digitally animated content. When holding a tablet or mobile phone with the Aurasma smart phone app over the frame, a film can be seen that explores potential user applications for this augmented reality app. It demonstrates how it could be used to facilitate participation or share digital messages by means of the cloth.

‘Cultural Fabric Africa’ is about the potential of African print fabric to support cultural sustainability through design in the context of changing patterns of consumption.

To watch film click image or download free Aurasma app to screen image

To watch film click image or download free Aurasma app to screen image

When setting out to undertake field research on the cultural values of print fabrics in Mozambique in early 2016 I intended to make an investigation into opportunities for ‘smart textiles’ my central objective. This was based on my own observations of seeing the accessibility of mobile and internet technology develop within the rural communities of southern Mozambique. Where in 2007 there was no network access in the village, rapid developments in infrastructure, technology and mobile phone providers changed this significantly within only a few years.

Talking with young women and men about their levels of phone use also made it evident that even where a phone was not owned, there were high levels of phone sharing amongst families and friends. Statistics show that ‘sub-Saharan Africa is forecast to see the highest growth of any region in terms of the number of smartphone connections over the next six years’ (GSMA Report, 2014:2). Recognizing this trend and seeing the enthusiasm that is evident in using mobile technology amongst the younger generation, it seemed appropriate to at least explore its potential to add meaning to African print fabric design.

The field of smart textiles has begun to demonstrate various possibilities of layering digital knowledge into the fabric of cloth and textiles through mobile technology. Kristi Kuusk has investigated textile craft applications in order to enhance connections between people and generations. As part of her PhD project she developed textiles with embroidered QR codes in a re-interpretation of traditional folklore costume. The QR codes lead to a digital narrative that creatively re-imagines stories and tales which are connected to traditional designs of Estonian Muhu skirts, bridging different cultural interpretations through tactile craft qualities with the use of new technologies (Kuusk, 2016:120). Through another prototype she demonstrates the integration of augmented reality to create virtual bedtime stories on children’s bedsheets that come to life when holding a tablet or phone over the print design on the sheet (Kuusk, 2016:48).

Augmented reality trials prior to field research trip, November 2015

Augmented reality trials prior to field research trip, November 2015

Studies such as these open up possible ideas of how traditional textiles in low-tech communities could become ‘smart’ textiles by adding digital content. Free mobile phone apps, such as augmented reality apps or QR code scanners, allow the investigation of such processes without the need for expert technical know-how and make them available to a broader range of users. Objects with a visual detail such as textile print patterns can be used to trigger videos, sound or photographic images recorded with mobile phones and can be shared amongst people.

However, when challenged to transfer these ideas into practice, I soon came to realise that such possibilities would remain theoretical speculations as there are still extreme limitations to access such technology in the context of rural villages. An important question also would be to ascertain whether in fact digital imagery and mobile technology would be suitable extensions to indigenous knowledge systems at all. What became clear at least was that these investigations would require a much more extended time frame than what was available for this research period, and would demand thorough investigation.

I have decided to include the presentation of the initial ideas through this design prototype to suggest it as an avenue for continued research opportunities.

To what extent does the design invite communication and/or meaningful interaction?

The design prototype could potentially create multiple layers of communication and interaction. On one level it could generate conversation and discussion about the process of embedding digital content. On another level it could generate meaningful interaction as content is added, shared and discussed.

To what extent is the design open to multiple levels of interpretation?

Interpretations are flexible as the content is flexible and could be freely altered and adapted.

How accessible is it and to whom?

Such design would only be accessible to someone who would have the right mobile device and knew how to access the app and the digital layer. It would imply that this level of acquisition and technical skill would be a requirement for engaging with such a design.

How could it be realised?

Provided the technology and technical skill was accessible it could be easily realised by communities themselves without changing production processes or even designs. Perhaps a challenge for textile designers could be to make the required technical skill available and evident through the design in order to reveal the potential avenues that users could explore.

What are its limitations?

Limitations of such a design would currently be an unequal distribution and high levels of exclusion to access. Unless such design ideas were guided by advocates who could bridge these discrepancies, it may add to increasing intergenerational and rural-urban disparity.

I appreciate how you draw inspiration from a concept connecting digital media with textiles and try to apply it in African rural conditions. Bringing the idea into a community you saw the value could be harvested. Perhaps now the people and the technology they own is not ready to use the proposed prototypes. Perhaps, it’s not the right way for them at all. However, you took it a step further and solved the question right at the context. You found out what works and what not, built on this knowledge and came back with enthusiastic community asking questions about their traditional garments and everyday cloth. Wasn’t this the goal 😉 ?